Smart Life Solutions that Improve Quality of Life by Solving Societal and Lifestyle Issues

The rise of information technology has led to the growth of very convenient services and has created an environment enabling daily needs to be met without outside help. But these trends have reportedly also weakened community ties at the same time. Hitachi has started a project called the Future Living Lab that promotes technology use by members of the community and self-directed community involvement. It is designed to help bring about Society 5.0—a vision for a world that values personal creativity. Based at the Kyōsō-no-Mori site created within Hitachi’s Central Research Laboratory in the Tokyo neighborhood of Kokubunji, the project has explored community member participation in the digital era by holding events that get members of the community involved in the cycle of local production for local consumption, and by creating electronic tickets tied to a new local currency for use at a local festival.

Released by the Japanese government in 2016, Society 5.0 is a vision for a coming era labeled the super smart society(1). But the government has not been completely clear about how Society 5.0 will differ from the information age of today (Society 4.0). Its vision leaves room for discussion about the new types of value that people will benefit from, and about the infrastructural systems for providing that value. While the information age has lowered communication costs, it has also created a number of problems. For example, ties to local communities have weakened, and community resilience has declined from the impact of individuals being forced to shoulder various risks by themselves(2).

Hitachi had already started promoting Vision Design activities by the time Society 5.0 had been dubbed the ‘Creative Society’ by the Japan Business Federation (Keidanren) in 2018(3). In contrast to the government’s super smart society, Hitachi’s Vision Design activities are positioned beyond smart society, promoting discussions with many people by presenting specific examples of infrastructural systems for the new era using video and other media(4). One of the themes highlighted by this Vision Design is trust. The widespread rise of digital technology has changed how people and organizations interact. In response, Hitachi has raised the question of how the use of digital technology might change the nature of trust-building among local communities. It is using workshops and other methods to research the functions that infrastructural systems should have in the future as it formulates and transmits its visions(5).

Despite the growing importance of vision-based discussion, real-world challenges cannot be overcome by workshop discussions alone. Hitachi has started a project called the Future Living Lab (FLL) that is designed to draw on real-world daily life to conceive future infrastructural systems and bring change to local communities.

A living lab is a type of community member participation project that gets members of the community involved in service planning and monitoring(6). Mika Yasuoka of the Technical University of Denmark runs a Danish living lab research project. She describes living labs as projects that are essentially about building confidence in creative ability and taking the initiative to design how the local environment is structured(7).

Hitachi’s living lab project has the word ‘future’ added to its name as a way to indicate the future-facing nature of its activities in response to Society 5.0, both for exploring issues and solving problems. The aim of the FLL is to explore community member participation in the digital era, along with the role that major corporations such as Hitachi can play in creating future-facing infrastructural systems. The Hitachi team that created the FLL’s vision starts by working with members of the local community to think about the future and doing what it can to achieve it. While customer collaborative creation projects are traditionally initiated by sharing issues organization-to-organization, the FLL project was initiated by having a smaller team and other individuals share their thoughts on the local community. Project participants will explore new values while overcoming challenges that are insurmountable using technology alone.

Grappling with issues caused by its aging population, falling birth rates, and accompanying decline in working-age population, Japan has become a well-known example of the challenges currently facing developed nations. Yusuke Kakei is a social design expert who has worked on projects for solving local issues in various regions. He classifies Japan’s municipalities into the three categories below on the basis of the conditions and issues they are currently facing in terms of geographic location, industries, population, and the like(8).

The Tokyo neighborhood of Kokubunji has the characteristics of category (2). Kokubunji is home to the Central Research Laboratory that contains the Global Center for Social Innovation – Tokyo (CSI). The FLL has started working here to discover the issues rooted deeply in the area, and explore future visions and solutions suitable for it.

Located in the western part of Tokyo, Kokubunji takes its name from the Musashi Kokubunji temple, which was built in the area in 741. The neighborhood developed into a residential suburb after World War II, and became recognized as a municipality (the city of Kokubunji) in 1964. The slightly growing population currently stands at around 124,000. In 2017, the city created a plan for revitalizing local industries that sets the following concrete goals with the aim of improving local attachment and increasing the city’s associated population(9).

In response to the conditions facing Kokubunji, the FLL is using the design and digital technologies that CSI excels at to research the creation of services for amplifying the level of interaction between community members and the community. The three phases below have been set to define the processes used to amplify the level of interaction.

In parallel to the activities being done by the FLL, the Hitachi Research & Development Group and Kokubunji’s municipal government have signed a comprehensive partnership agreement aimed at revitalizing the local community by creating innovations.

Kokubunji has been associated with farming for about 300 years, and is still home to fulltime farmers of vegetables, flowers, and other crops. Since 2015, the city has been developing its own system of local production for local consumption through a project called Koku Vege. Local produce is delivered directly from farms to about 110 local restaurants. But the project depends on ties to local farming, which is beset by a shortage of successors and shrinking farmland being converted to residential use. Maintaining ties to local farming will require greater interaction between the Koku Vege project and members of the community.

Seeking to promote a new culture in Kokubunji, Hitachi decided to collaborate with the Koku Vege project as a way to inspire ideas on how to create the infrastructural systems of Society 5.0. It approached Circular city Kokubunji (CCK), the nonprofit organization that handles delivery for the Koku Vege project. Hitachi and CCK shared the goal of getting community members directly involved in a system of local production for local consumption. The two organizations conceived a delivery method run by community members (see Figure 1), and created a vegetable delivery project named My Vegetables through community events held in November and December 2018.

The project involved participants picking up vegetables at public municipal facilities near train stations and delivering them on foot to restaurants, where the cooked produce could be eaten. It was designed to promote two of the three phases above. Phase 1 (understanding the local community) was promoted by raising community awareness of the Koku Vege project, and Phase 2 (engaging with the local community) by involving community members in delivery. Members of Hitachi and CCK worked together to create a series of service designs (see Figure 2). Hitachi created the web application used by participants, and designed points of contact such as place mats and pamphlets (see Figure 3).

Over the project term, about 360 people visited the venues and 76 took part in delivery. Questionnaires showed that about 95% of the respondents were satisfied. Feedback solicited in the questionnaire also showed a positive response to the idea of using local production for local consumption to build a network of community members. But with only 26% of respondents saying they wanted to take part in Koku Vege support activities, there are still challenges to overcome for turning the project activities into permanent participation. The farmers and restaurants that assisted the project were eager to play a greater role in the future, showing that the project had amplified the level of interaction for fostering and assisting the local community.

Fig. 1—Community Member Delivery Method Used by Koku Vege: My Vegetables Members of the community who were previously consumers played a central role in the cycle of local production for local consumption.

Members of the community who were previously consumers played a central role in the cycle of local production for local consumption.

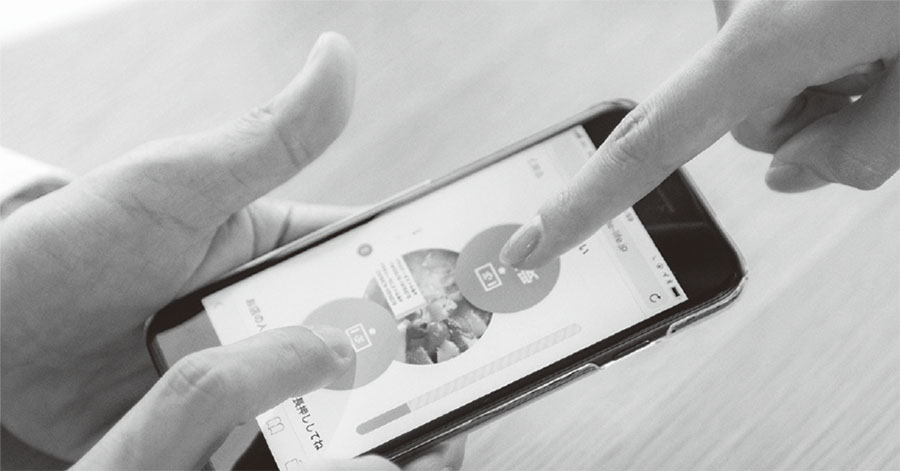

Fig. 4—User Interface for Electronic Ticket Payment The payment is made when the patron (payer) and server (payee) press and hold the buttons simultaneously for a set amount time.

The payment is made when the patron (payer) and server (payee) press and hold the buttons simultaneously for a set amount time.

Kokubunji’s internal-external retail sales ratio was 0.507 in 2014(9), indicating more consumption outflow to other areas than consumption within Kokubunji. Since cities such as Tachikawa city and Musashino city (containing Kichijoji) are located nearby, few shoppers may prefer Kokubunji. Getting people to spend money in the city is a key requirement for revitalizing the local industries. To do so, a citywide payment method called Kokubunji Card was created in 1999, but new user registrations are reportedly declining and users aging.

The FLL wanted to create a new form of local currency that would allow value to circulate in the community. As the first step toward achieving this goal, the FLL worked with the organizer of an annual local festival to create electronic tickets for the event. Named Bunji Bar, the festival is held every summer by a retailer’s association. As with the Koku Vege project, the relationship between Hitachi and the organizer grew out of a shared enthusiasm for the project’s goal. Both the researchers and the store owners were eager to create a new local currency.

One of the issues targeted by the electronic ticket project was solving some of the problems associated with conventional paper tickets such as ticket-counting and loss. But the project was more focused on emphasizing how payments made in drinking/dining establishments could serve as opportunities to build ties to the community.

When using alternatives to legal currency, there are many payment services that can be used without creating a local currency. But instead of faster payments, Hitachi felt the project needed a way to help build a relationship between the drinking/dining establishment and community members with every payment transaction.

The primary characteristic of electronic tickets is the payment user interface. The project handled payments by using the smartphones of community members patronizing the drinking/dining establishments. Two payment buttons were displayed side by side on the screen, and the community member and server both had to press and hold these buttons together for a set amount of time to make the payment (see Figure 4). This approach gave both parties a little bit of time for face-to-face conversation by bringing them into physical proximity with each other. Payment security was guaranteed by using blockchains. Project demonstration testing continued after the end of the Bunji Bar festival with the help of the local drinking/dining establishments. Some updates were made, such as allowing participants to recruit corporate sponsors to pay for premiums. The establishments accepting the electronic tickets and their distribution share in 2018 were both limited in number, but the project was praised by both the establishment owners and patrons, so it was considered a successful first step toward creating a new local currency.

Fig. 5—Workshop with Kokubunji Municipal Office Staff The workshop provided an unrestricted atmosphere for sharing the challenges facing the city and brainstorming ideas.

The workshop provided an unrestricted atmosphere for sharing the challenges facing the city and brainstorming ideas.

The FLL aims to get a greater number of community members aware of the challenges being faced and to steadily apply solutions to the community. It has been working on activities at the Kyōsō-no-Mori(10) site that opened in FY2019. One example is the Kyōsō-no-Mori Partnership Program, a project about community ties that uses the facility’s project room and staff from the Kokubunji municipal office. A workshop was also held with about 20 municipal employees. It was designed to teach participants about Society 5.0 and to identify the issues facing the city (see Figure 5). The FLL held a symposium in Hitachi Baba Memorial Hall in October 2019 to which the mayor of Kokubunji was invited. Through these activities, the FLL will continue to help overcome community challenges.