COVER STORY:Extra Contribution

Based on strategies such as Thailand 4.0 started in 2017, Thailand is now accelerating digitalization in various fields. This extra contribution from the Digital Economy Promotion Agency of Thailand (depa) introduces what a smart city is and Thailand’s initiatives to achieve it.

In recent years, the term “smart city” is heard being used in different ways. Many federal and local governments can often be heard proclaiming the need to expedite the economy “through smart cities.” Also witnessable are private enterprises’ advertising their new plans to boost growth with the keyword “smart city.” It is undeniable the term has gained significant traction in the global socioeconomic lexicon. Events including everything from an international exhibition to a local college’s hackathon use “smart city” as the key branding strategy. But what exactly is a “smart city?”

A smart city is commonly understood as an urban environment that makes use of technology and innovation to enhance its capacity, managerial efficiency, and resource utilization. In contrast to a “traditional city,” which operates based primarily upon the existing physical infrastructure and laborious non-digital processes, a smart city makes use of data to drive automation, enhancing the livelihood of the residents. As a result, a smart city helps to decrease the unnecessary spending of its residents, emphasizing good design and participation from all sectors in society. The key urban development concept is to make the city more resilient, with the development goal of sustainably improving the quality of life (QoL).

As a global trend, cities around the globe are in high demand due to the shifting of the global economic mode from producing goods to providing services. While many would agree that cities are hotbeds of innovation, it is undeniable that cities also create trash, pollution, and consume an insurmountable amount of energy. Once and for all, this article aims to outline the concept of a smart city based on the research and development of the Digital Economy Promotion Agency of Thailand (known internationally as “depa”) and the Smart City Thailand Office. This article, it is hoped, will serve as a springboard for everyone, not only for those who are interested in better understanding such an important and popular concept, but also for those who may want to “join forces” in positively shaping and re-shaping the world in which people live.

First and foremost, it is important to agree on one thing — that a “smart city” is a process, and not a result. The idea is that no city reaches the status of a smart city by simply ticking all the boxes. As with humans, “smart” refers to the ability to comprehend a situation in a meaningful way, such as in adapting and transforming, to cope with and improve the changing world. The idea of a smart city “as a process,” therefore, entails a set of milestones and conceptual framework pertaining to systematic, consistent, and proximal development.

By this definition, all cities are already “smart” in some ways since the idea of “smart” is part and parcel of the ability to survive in a changing world. Cities, however, can always improve to which the understanding of the idea of smart city “as a process” is crucial. Boiling down to a magic number of three, here are the three basic concepts encompassing the smart city:

Cities are for people. If not for people, then there is no need for cities to exist at all. So, contrary to some popular perceptions that cities are all about technology, the belief is that it is about the needs of the residents. A “smart city” is one where its residents get access to abundant livelihood, employment, lifelong learning, and entertainment — as in the LLWP or “Live-Learn-Work-Play” concept.

So, by placing citizens at the center, it might not always be the case that cities need the most cutting-edge technology. What cities need, instead, may be as technological as appropriate. A smart city should not be an urban environment whereby residents confront the dilemma of technology daily. For example, cities that require residents to be hooked on their smartphones 12+ hours a day in order to be “smart” cannot be good for the health and wellbeing of the residents.

On the other hand, smart cities are those that use the appropriate technologies to enhance the quality of life in the background, such as automated traffic, energy efficiency, and integrated healthcare systems. Residents may not feel that “something” is working for them and on their behalf, which is fine as long as their level of wellbeing and livelihood is increasing. In this sense, the evidence of success lies in the measurable indicators such as less travel time, worry-free access to healthcare, and more spare time.

To expedite the process, it is important to synergize the “superpower” of the people, public, and private sectors in the fashion of “People-Public-Private-Partnership” (PPPP). The commonly used term is just PPP, but the “P for the People” is included in the equation, as many recent instances of the successes, and especially the failures, of smart city projects worldwide have demonstrated the crucial need to communicate with the people, therefore galvanizing their support in the process (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 — Identifying Citizen’s Needs for Smart Cities

“Because citizens are at the center”; therefore most crucial to the People-Public-Private-Partnership (PPPP) process is always defining the needs of the citizens “from their own perspectives.” This photograph shows how tools such as design thinking and business model canvas are used to identify the needs of citizens.

“Because citizens are at the center”; therefore most crucial to the People-Public-Private-Partnership (PPPP) process is always defining the needs of the citizens “from their own perspectives.” This photograph shows how tools such as design thinking and business model canvas are used to identify the needs of citizens.

Finally, as tempting as it may be to think of a smart city in terms of a series of “data-driven digital platforms,” cities still consist of connected physical spaces. So, the simultaneous development of both the physical and digital infrastructures is required so that the demands and supplies of physical goods can travel to meet one another after the price and the service have been agreed upon on the digital platforms.

In the context of Thailand, the government realizes the importance of improving cities as places for productive residents. It, hence, places a great emphasis upon the distribution of growth in all regions of the country, as evident in the Twenty-Year National Strategy, the 12th Economic and Social Development Plan, Thailand 4.0 Driving Model and the Digital Thailand for Economy and Society Development Plan. Building smart cities is Thailand’s urgent national agenda with the goals of lessening inequality and boosting growth in all regions.

With the “people first” mindset, a smart city is a livable urban environment, effective in its organization and management. Each city will choose the type of smart city it aspires to become, whether that be a modern city, a livable city, or a city with a traditional sense of identity and culture, all with the basic infrastructure that provides citizens with the sense of convenience in transportation, water, and electricity systems — as well as digital technology. All of these efforts will lead to a transition to 100 smart cities that foster well-being, livelihood, and sustainability by the year 2022.

Currently housed at depa, the Smart City Thailand Office has been set up to oversee the operation and progress of smart cities in Thailand. Under the guidance of the National Steering Committee on Smart City currently chaired by a Deputy Prime Minister, the Office bundles various forms of incentives for interested cities, such as tax benefits from the Board of Investment (BOI) of Thailand and non-tax benefits such as the Smart Visa for a skilled foreign workforce, technological sandbox for new technologies, and incubation and accelerator programs for both cities and solution providers.

A city with smart city aspirations, therefore, would propose to the Smart City Thailand Office to engage in the smart city program with the ultimate goals of being endorsed by the National Steering Committee on Smart City. To get there, these cities will be lively and dynamically incubated by depa and partners through various programs and measures. Currently (October 2020), there are proposals from 40 cities who are officially in “depa Smart City Promotional Areas.”

As the “depa Smart City Promotional Areas” process goes, it sets up a mnemonic device “Two-Five-Seven” to help people remember key information about the process. The next section starts with the first number, “Two.”

Smart city candidates are first asked to determine which type of smart city they aspire to become. Determining which type is a result of both the citizen-centric understanding of the city and the evaluation of its potential in development, whether that be socioeconomic, educational, or industrial. To be developed into a “Smart Livable City,” the existing city needs to incorporate and integrate the technologies and innovations, as needed by its residents, that vary by the city’s specific contexts, such as infrastructure, social services, housing, recreational areas, and commercial resources, including the design of urban spaces contributing to the rich existing culture, tradition, and identity of the city as a whole.

While a Smart Livable City makes use of technology and innovation as needed by its specific contexts, a “New Smart City” focuses on development based on land (e.g., greenfield or brownfield), labor, and ample opportunity for new development in line with certain national policies, such as in the case of the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) of Thailand (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 — Smart Livable City and Smart New City

Illustrations comparing dominant characteristics of the Smart Livable City to those of the Smart New City.

Illustrations comparing dominant characteristics of the Smart Livable City to those of the Smart New City.

Based on the extensive research and development of the Smart City Thailand Office, there are five criteria for measuring the potential of a city’s proposed smart city program:

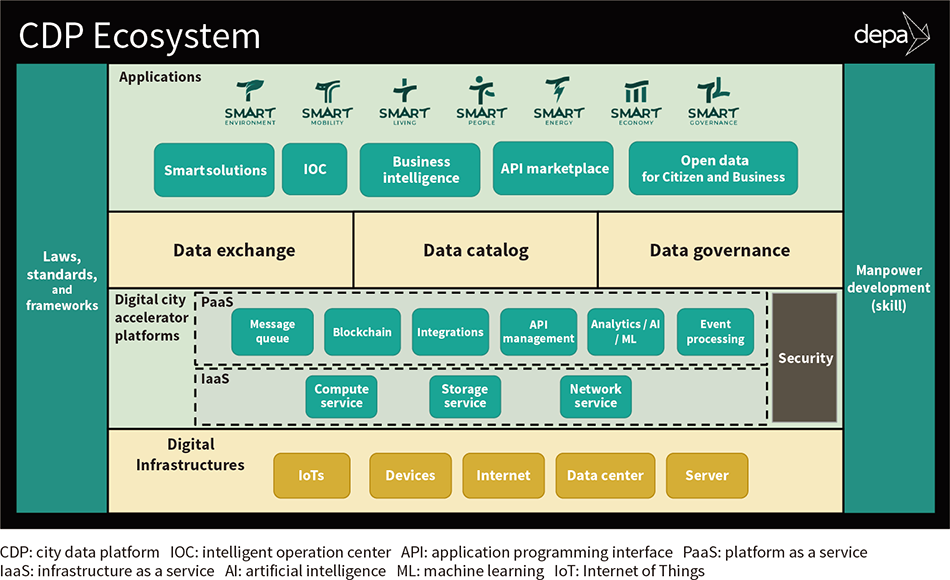

Figure 3 — CDP Diagram

The City Data Platform, commonly known as “CDP” or in different contexts as Urban Data Platform or Data Analytic Platform, is a system that integrates the large amount of data in cities to give a holistic view of a city’s condition so that the services to meet the needs of the citizens can be provided in a timely manner – ideally in real time. Collecting data from demand-side, supply-side, and analytical and standardization streams, CDP is one of the five criteria for Thailand’s smart city development.

The City Data Platform, commonly known as “CDP” or in different contexts as Urban Data Platform or Data Analytic Platform, is a system that integrates the large amount of data in cities to give a holistic view of a city’s condition so that the services to meet the needs of the citizens can be provided in a timely manner – ideally in real time. Collecting data from demand-side, supply-side, and analytical and standardization streams, CDP is one of the five criteria for Thailand’s smart city development.

Often, cities are encouraged to use tools from both the Design Thinking and Business Model Canvas (BMC) schools of thought that are widely used among creative entrepreneurs. These tools are useful as they facilitate not only productive communication among the stakeholders, but also provide a layout of the overall process of smart city development and promotion.

As a process, the smart city is characterized by seven domains, which serve both to guide operation and to benchmark success (see Figure 4). Also based on extensive research, these seven domains of smart city are seen to encompass all value, virtue, and viability of a smart city program.

Figure 4 — Seven Domains Logo

This figure shows the design of the logos of the seven domains of Smart City Thailand.

This figure shows the design of the logos of the seven domains of Smart City Thailand.

This article serves both to provide the ground for the understanding of Thailand’s smart city effort and an open invitation to join forces to foster positive socio-environmental change. The hope is that this paper has highlighted the importance of the concept of a smart city as the “key umbrella” both in promoting the innovation industry and in supporting the rapidly changing society. In this context, depa serves as “the hub” in the development of both digital manpower and technology, including standards, regulations, and guidelines in materializing smart cities.

To close, it is useful to be reminded that smart cities are citizen-centric. Contrary to some popular perceptions, smart cities do not always have to be ultra-high-tech. Instead, smart cities prefer “practical technology” that fosters people’s wellbeing and livelihood (see Figure 5).

Figure 5 — Process of Understanding “Smart City Two-Five-Seven”

In the end, a smart city is where everyone who is involved in the process is happy with the process as well as the result. This photograph represents the process of understanding the “Smart City Two-Five-Seven” with the citizens by engaging and empowering them to create the future of the cities in which they themselves would like to live.

In the end, a smart city is where everyone who is involved in the process is happy with the process as well as the result. This photograph represents the process of understanding the “Smart City Two-Five-Seven” with the citizens by engaging and empowering them to create the future of the cities in which they themselves would like to live.

The key to a successful building of smart cities, therefore, is the understanding of the demands and needs of residents “from within.” As the hub, depa connects the central and local governments, private sectors including startups, academic and research institutions, and external partners in both the ASEAN region and beyond.