November 2020

What sort of world can we expect to inhabit after the coronavirus pandemic has passed? Many views have been exchanged on this subject. My own is that we will see a world of “many coronas,” which is to say one characterized by the ongoing emergence of (new) threats such as that posed by COVID-19. This will be a world where new crises will be routine, crises of a nature that could not be predicted on the basis of past knowledge and experience, encompassing not only pandemics caused by infectious disease, but also natural and man-made disasters resulting from changes in global, social, and urban environments together with the economic and political crises that come in their wake.

While excessive globalization and changes in the global environment and in ecosystems are among the causes offered for the spread of coronavirus, underlying these is the philosophy that has prevailed over the 200 or more years since the Industrial Revolution of giving priority to economics, which is to say that it represents a high price that humanity has to pay for our sustained self-interested actions that have caused the separation of society and the economy.

Looking back, this discord between the environment and economy has been a continual undercurrent in society during modern times, as exemplified by the Limits of Growth published by the Club of Rome in 1972. While the recent interest of corporations in corporate social responsibility (CSR); environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG), and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) represent attempts at mitigating these issues, this discord has now manifested as the significant pain caused by the coronavirus pandemic. It is likely that this trend will only accelerate in the future.

Shuntaro Ito, a notable Japanese scholar of the history and philosophy of science, has described our time in the 21st century as a time of environmental revolution. The extent of this is not limited only to concern for environmental problems; rather it is based around overcoming these problems and represents a fundamental turning point in human history that follows on from past revolutions, namely the Anthropic Revolution that gave rise to modern human beings about 200,000 years ago, the Agricultural Revolution that introduced crop and livestock farming, the Urban Revolution involving the emergence of cities, the Spiritual Revolution that gave rise to the world religions of the East and West, and the Scientific Revolution that gave us the world of today. What is significant about this is that it involves revising our idea of humanity’s dominion over nature, the conception and philosophy of nature that underpins science and technology as well as modern culture, and instead seeking a new form of civilization that is reconciled with the ecosystem as a whole, of which human beings are one part.

In other words, as we face numerous challenges of a global scale, we are entering a time for rethinking our past philosophies and practices of prioritizing economics and plundering nature and its resources, and for seeking out new ethics and ways of life that reconnect society and the economy. For this reason, we should expect innovation itself to become our core task.

In terms of corporate management, the environment for management is turning into unpredictable chaos. This has been described as a time of volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA), a world where past strategies and business models can no longer be relied upon. More than this, it is also far from unusual for dependable businesses once considered inviolable to be rendered obsolete and to cease to exist. In the future, all companies will be under pressure to put innovation at the heart of their management and to initiate their own changes. This applies to all activities, not just particular areas such as the launch of a new venture, including core and other existing businesses, associated spin-off businesses, and ventures into entirely new areas, such that this portfolio of businesses likely becomes an issue in itself.

What form should be taken by innovation for the 21st century? Consider, for example, the following words by Albert Einstein:

“We cannot solve our problems with the same level of thinking that created them.”

In other words, a revolution in consciousness is needed if we are to resolve the global challenges discussed above, and rather than strategic methods or practices, we should be reconsidering the nature of our thinking and how we look at things. It follows then that innovation involves not focusing solely on technological destruction and creation that has no bearing on our daily life, but rather building new subjective world views that question how we live and how we can create value that is of use to society. This relies entirely on our grassroots human intellectual capabilities.

This coincides with the nature of knowledge societies in which everyone thinks like an entrepreneur and a better way of life is built through ingenuity and invention, a point that is made by Peter Drucker in his book, Innovation and Entrepreneurship. In the agrarian and industrial societies of our past, the primary economic actors were the feudal lords and capitalists who owned the land, machinery, and other means of production. In a knowledge society, in contrast, our brains and talent are the means of production and, as a result, it is individuals who now drive the economy. This is why the knowledge of autonomous city dwellers who collectively form networks is now said to be the wellspring of value.

Thinking about it, 20th-century innovation was based primarily on the supply-side logic of innovation spreading from upstream to downstream by way of corporate research and product development, underpinned by discontinuous technological advances. In contrast, the model of future innovation calls for taking the opposite path, being based on a demand-side logic that has empathy and insight into customers and wider society as its starting point, seeking societal and environmental sustainability and humanistic value. That so many companies are taking an interest in design thinking that is inspired by empathy with customers is a response to this modern trend.

In practice, this is also bringing major changes to the nature of economic value. Manufacturers in the past have sought to add value to products by enhancing their functionality, and when unable to differentiate on this basis, they have also added semantic value as expressed by the idea of a transition from tangibles to intangibles. In either case, however, this is still driven by supply-side thinking that sees the world in terms of tangible things.

In contrast, what people are tacitly seeking now is not additional functionality or value that has no intrinsic connection to their way of life, but rather humanistic and aesthetic value by way of solutions and ideas that suit their lifestyle and life circumstances. It is becoming even more difficult for companies to provide customers with value through their products alone, such that it will be essential in the future that they adopt an approach that achieves this through the formation of market ecosystems in partnership with various other players who share a common purpose. The concept of an industry will likely also undergo a change away from being defined by its products and instead come to be synonymous with market ecosystems.

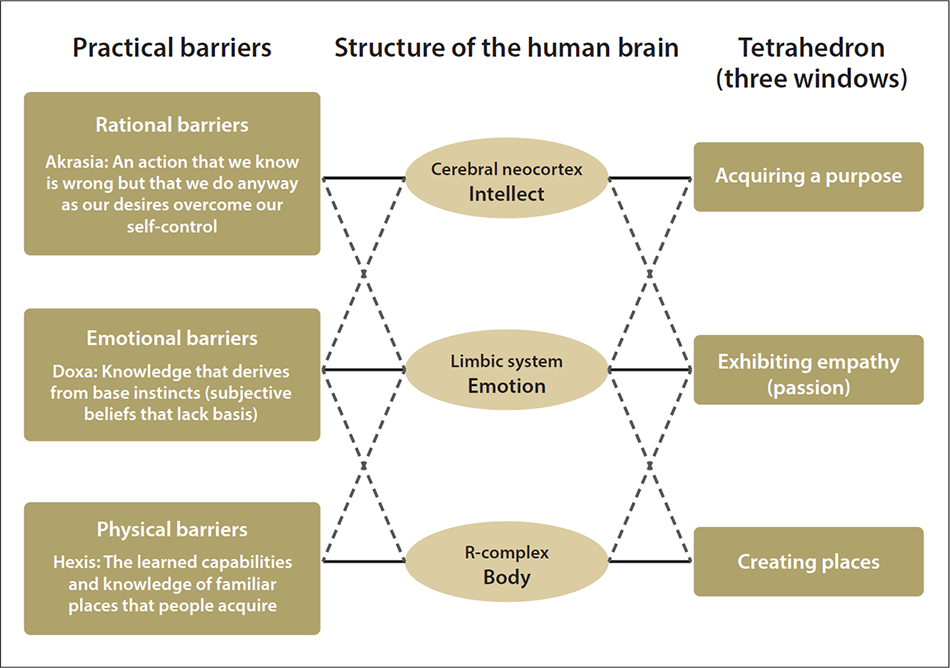

Meanwhile, human nature is such that people respond to this state of crisis by clinging to the status quo and through their own internal contradictions, indecisiveness, and predisposition to resist change are inclined not to act. Viewed in the light of neuroscience, the structure of the human brain (the rational brain, emotional brain, and motor function brain) is such that human beings are recognized as facing three barriers, namely barriers of rationality, emotion, and body.

Along with new perspectives, three other factors provided by the revolution in consciousness discussed above are important for breaking through these barriers. These are purpose, empathy (passion), and place and can be thought of as three windows that provide the openings for putting innovation into practice. I call these the “four Ps that enable human innovation” and the “innovation tripod” (three legs of a tripod forming a tetrahedron). While it goes without saying that the “place” represented by the starting points of purpose and empathy are important for achieving innovation that derives from customers and society, I would also like to consider the following more practical measures.

Barriers to Putting Innovation into Practice and the Three Windows

The first “barrier of rationality” means a focus on immediate outcomes and a lack of understanding of the real purpose and long-term risks. For example, does an excessive focus on numeric targets or performance indicators cause you to lose track of your ultimate purpose? In the current environment where companies are expected to fulfill their role as members of society, companies that pursue social goals are starting to steadily improve returns while those that purposelessly pursue profit for their own gain lose profitability.

The idea of “responsible innovation” has been widely adopted in Europe, meaning that long-term investment in research and development can only maintain its legitimacy through its use to resolve societal challenges.

The business models of many companies are now reaching their use-by dates, thereby creating a need to find new value and formats, yet another reason why it is important to revisit the question of what they are seeking to achieve.

Moreover, having a purpose can be a driving force inside organizations. A definite purpose that has social significance and for which the scope, actions, and outcome can be clearly expressed and shared encourages everyone to act and collaborate on their own initiative, thereby boosting the collective knowledge of the organization. More specifically, it is useful to think of purpose in terms of a stratum in which purpose is translated into action by regularly reiterating the overall long-term purpose as you go about assembling the intermediate purpose to be achieved, a process that also involves going back and forth between the purposes of the organizations, groups, or individuals who possess particular resources and skills. Here, the overall purpose can be thought of as representing the common good whereas the intermediate purpose is the “when, where, and what” that represent the project mission. We have adopted the term “purpose engineering” to describe this methodology for turning purposes into action.

The second barrier, that of emotion, refers to predispositions and biases that lack justification. These act as a major impediment to putting innovation into practice. Examples include preconceptions or an inability to see beyond the successes of the past, such as the ideas that Japan is strong in manufacturing or suffers from a lack of creativity (being more suited to the incremental improvements of kaizen). On the other hand, it is the power of passion that can overcome these impediments and it is having a strong sense of empathy or indignation with the actual circumstances facing customers and other parts of society that spurs us to action.

Design thinking that utilizes observation, ideation, prototyping, and storytelling is one such knowledge creation process that derives from this power of empathy. As noted below, it corresponds directly to the processes in the world-renowned socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization (SECI) model of knowledge creation proposed by organizational theorist Ikujiro Nonaka.

Comparing the two approaches like this makes it clear that socialization based on empathy is also an important aspect of design thinking. Without it, the process becomes one of merely mechanically working through a sequence of steps that will not deliver any meaningful discoveries. The current interest in art thinking is a reaction against this tendency of design thinking to become no more than a mechanistic procedure, and in the sense that it reflects a desire to restore capabilities rooted in human emotions such as empathy and intrinsic motivations that were downgraded in importance by the emphasis on theoretical analysis that dominated in the 20th century, one can say that in practice they share a common nature.

The third barrier, that of the body, refers to instinctive or ingrained behavioral patterns that are hostile to change. Achieving innovation requires that we free ourselves from past practices and habits (as exemplified by existing businesses). Unfortunately, most corporate organizations are optimized to the needs of their current operations and find it difficult to achieve change if they stick to the same ways of working. On the other hand, moving to a different “ba” or place frees us from ingrained attitudes and thinking, or as the philosopher Kitaro Nishida said, “People create their environment; the environment creates people.”

Nevertheless, innovation does not only arise out of the ideas and thinking of individuals. What is also needed are places where knowledge can interact that encourage interplay among people and between people and the environment. Some companies are already establishing their own spaces for implementing this creation of new places, with examples that include future centers for exploring ideas about future trends, innovation centers that engage in prototyping based on such ideas and on the company’s own technologies and other resources, and living labs that undertake live social experiments targeting neighborhoods and communities. This action also serves as an important declaration of intent by managers to others in the company and further afield. The essence of this will remain just as important in the post-corona world.

Ideally, if these places are to prove their worth, then rather than trying to do everything at one center, it would be better to have intermediary hubs that are open to various other companies and organizations, and that can work together with each fulfilling its own particular role and function. The true significance lies in their transcending these boundaries and going beyond the scope of individual companies to engage in dialogue as members of society. In actual practice, it is important that these places retain their autonomy while also spanning the various head office resources and encouraging free and open debate as they engage with society; in other words that they avoid becoming an outpost that keeps the company’s core business unchanged. What is needed, rather, is to act in ways that also target innovation in this core business.

Finally, I would like to tell you about the paradox of Buridan’s Ass, something I refer to often.

This is the story of a hungry donkey. The donkey is confronted with two stacks of hay, both exactly the same distance away and both of the same quantity and quality. When the donkey attempts to apply reason and assess the situation analytically, it always comes to the conclusion that both stacks are the same, with the result that it ends up starving to death in a state of indecision.

While the story may sound comical, does it not also describe companies and other organizations that fail to act because they persevere with analysis and theoretical debate without ever coming to a decision?

As noted earlier, we are in an era of “many coronas” in which crises are becoming the norm. The way that an over-reliance on reason, analysis, and theory has paralyzed our thinking at this turning point for civilization risks our getting suspended in time just like the donkey. Moreover, in an unpredictable world, we cannot expect to find answers by analysis alone. We need to rouse our free will and take a first step forward, using what we learn by doing so to inform our next step, thereby moving closer to success and the achievement of our purpose through a process of trial and error. In other words, innovation is the work of trial and error.

Rather than essentialism and “singularity” thinking, the attitudes behind the assumption that data reigns supreme (namely that there always exists an essence of things along with unique answers), what will without a doubt underpin this voyage into the unknown will be existentialism and pluralistic thinking that involves going out into the world as it is to explore its possibilities.

The science and technology that built the modern society do not in themselves come with a purpose. It is up to human beings to decide how these tools are used and human intent and judgement will always be needed to achieve wellbeing and a prosperous society. In other words, changes in the world come about when I as an individual choose to act on the basis of my own will.

Hitachi’s Social Innovation Business that seeks the collaborative creation of social, environmental, and economic value on the basis of linking society and the economy together is very well placed at this time when the environmental revolution is getting underway in earnest. I look forward to Hitachi’s creation of new value based on human intentions reinforced by new perspectives and by “purpose, passion, and place.”