Introduction

Hiroshi Ohashi

Hiroshi Ohashi

Vice President and Professor of Economics, the University of Tokyo

Graduated from the School of Economics, the University of Tokyo. Obtained a PhD in economics from Northwestern University in the USA in 2000. Following appointments as Professor at the Sauder School of Business at the University of British Columbia in Canada, Associate Professor at the Graduate School of Economics and Graduate School of Public Policy at the University of Tokyo (becoming a Professor in 2012), and Dean of the Graduate School of Public Policy, he was appointed to his current position in 2022. His research fields are industrial organization and competition policy. He has served on various committees, including the Advisory Committee for Natural Resources and Energy and the Electricity and Gas Market Surveillance Commission. He is a recipient of the Miyazawa Kenichi Memorial Prize (Fair Trade Association) and Jiro Enjoji Memorial Prize (Japan Center for Economic Research). His publications include “The Economics of Competition Policy” (Nikkei Inc., Tokyo).

The perspective on measures to address global warming is undergoing a significant shift. Whereas the emphasis was once primarily on the burden these measures represent, the current global acceleration towards decarbonization has sparked a different viewpoint in Japan. Increasingly, these efforts are seen, not as a burden, but as an opportunity to create new business models and transform the country's industrial structure. A clear sign of this momentum can be seen in the emerging view that carbon pricing can be a driving force behind a green transformation (GX) of the entire socioeconomic system that will speed up the transition to carbon neutrality.

In Japan, the Act on Promotion of a Smooth Transition to a Decarbonized Growth-Oriented Economic Structure (GX Promotion Act), which authorized the issuing of GX transition bonds and introduced carbon pricing was passed on May 12, 2023 by a plenary session of the House of Representatives*1. It will see the issuing of JPY20 trillion in GX transition bonds over the next 10 years until 2032, providing support for the research, development, and adoption of new technologies for non-fossil energy (including hydrogen and ammonia, renewable energy, and nuclear power) as well as energy efficiency and carbon fixation.

The GX transition bonds are set to be repaid by the revenues generated from carbon pricing. In Japan, a global warming countermeasure tax has already been introduced. Although not directly proportional to carbon, an “implicit carbon tax” is also levied on fossil fuels, averaging around JPY 6,000 per ton of carbon(1). Against a background that includes the anticipated introduction by the European Union (EU) of its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), the GX Promotion Act will introduce carbon levy and emissions trading as measures for reducing carbon emissions.

Carbon pricing will be levied on upstream suppliers such as fossil fuel importers, with introduction to begin from FY2028. The trading of emissions on a trial basis within the GX League is scheduled to get fully underway from FY2026, with auctions among electricity generation utilities to begin once renewable energy levies reach their peak*2.

While details such as the level of carbon pricing are not yet finalized, putting an appropriate price on carbon is essential if practices such as carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) are to be pursued commercially. Along with eliminating duplication with existing implicit carbon taxation such as energy efficiency regulations and energy taxes, it is also desirable to adopt systems that are neutral with regard to different technologies or forms of energy, something that can be done by making explicit the actual cost of carbon, even where it is not proportional to emissions.

This article discusses the measures to promote investment in GX that are a prerequisite for carbon pricing, looking at the key considerations through a policy-making lens.

- *1

- This was revised by both houses of parliament before the final version was passed by the House of Representatives.

- *2

- In the GX Promotion Act, this is stipulated to commence in FY2033.

Characteristics of GX Investment

Along with the announcement in October 2020 that it would seek to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, Japan also indicated in April 2021 that it would adopt an additional target for FY2030 of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 46% from their FY2013 levels while also pursuing strategies for the stretch goal of 50%.

As Japan moves toward carbon neutrality while also contributing to the achievement of this goal globally, increasing the total sum of public and private investment over the next decade to more than JPY150 trillion will require individual industries to develop the alternative practices needed to transition to carbon neutrality.

Carbon pricing is a useful tool for encouraging behavior change by those companies that have such alternative technologies for carbon neutrality available to them. For those companies or industries where such alternatives do not exist, however, simply levying a carbon price will likely result in them moving offshore (“leakage”). This is why the development of new technologies for those industries that currently lack alternative technologies requires support that is integrated with regulation.

Even once these alternative technologies have entered practical use, it is likely that while some companies will be early adopters, others will lag behind. Emissions trading is being looked at as one mechanism for controlling emissions that can mitigate the unfairness resulting from these different levels of action. Carbon neutrality is the state in which the quantities of anthropogenic emissions and sinks (absorption or elimination) are in balance at a national or global level, even though these emissions and sinks will be attributable to different actors. A requirement for this is that these different actors are able to trade these quantities in the form of credits. Given that the introduction of mechanisms for controlling emissions will likely be needed in the future, the work being done by the GX League involves establishing a voluntary emissions trading scheme for achieving targets companies have set for themselves so that it can serve as a preparatory step toward a future such scheme. It is also fair to say that the measures in the GX Promotion Act are what the GX League was aiming for in its work, extending to small and medium-sized businesses as well as large corporations.

Formulation and Evaluation of GX Investment Support Policy

The sort of technological development that comes with a high degree of uncertainty and in which private-sector companies are hesitant to invest their own funds takes years to complete and tends to require large amounts of money. Given these characteristics, measures to support GX investment call for a policy mindset that is different from what has prevailed in the past.

In simple terms, the three requirements of past policy-making have been a single-year focus, transparency, and fairness. That is, budgets must be spent within the financial year and cannot be carried over (single-year focus), provided that reviews are made public it does not matter if they are not used to inform subsequent projects (transparency), and rather than providing large amounts of investment funding to particular companies or industries, it is common practice to spread funding thinly across as many companies as possible (fairness).

What is needed for GX investment support is to break away from these three criteria. This means providing a limited number of companies or industries with funding that runs for multiple years through periods of socioeconomic uncertainty*3 (addressing the “fairness” and “single-year focus” criteria respectively). Given that the needs of GX will change with changing socioeconomic conditions, the policy-making stage needs to allow a certain degree of tolerance so that minor course corrections in the direction and objectives of GX investment can be made in response to the needs of society and the economy.

This is called “agile policy formulation.”(2) To enable this, mechanisms need to be built in at the policy-making stage that allow for policies to be modified during implementation, with the collection of data in real time and appropriate evaluation practices that are not tied to the financial year. The sort of dynamic policy formulation and evaluation that provides agility is especially needed when funding GX investment that is expected to run for five years or more. Work on this sort of evaluation should facilitate action on digital transformation (DX). This approach to GX should also help avoid the tacit public demand for “policy infallibility,” (the notion that targets, once set, should never be changed) and undo the spells that this casts (to address the past issues with “transparency”).

- *3

- The applies not only to GX, but also to other corporate assistance such as semiconductor industry support for reasons of economic security.

Programs for GX Investment Support

Another issue that arises when providing support for GX investment is the question of what criteria and key performance indicators (KPIs) should be applied to policy implementation when there is a high level of uncertainty and a need for agility. One possibility is to base responsibility for policy outcomes on results, for example, as outcomes may be different depending on external circumstances such as market conditions, domestic and overseas technology competition, or personnel changes. It has already been noted that the use of results-based criteria to evaluate such projects, which are not easily replicable, poses many problems(3).

Consider an example in which the criterion used is improvement in energy productivity. In such an example, it may be difficult to distinguish energy productivity improvement from a decline in labor productivity or the movement offshore of high-added-value manufacturing. Likewise, if profitability is used instead, the risk is a failure to recognize the benefits of decarbonization investments that take a long time to be reflected in the bottom line, causing such investments to stall.

Basing evaluation on inputs instead of these outcomes or outputs, on the other hand, is prone to moral hazards and it will likely be difficult to recognize whether GX investment is really being done on a best-effort basis. Given the difficulty of evaluating support policies based on the investment process, it suggests that more work needs to go into finding new policy formulation and assessment practices for the monitoring and evaluation of GX investment. If evaluation based on outputs and outcomes is difficult, it may be that this calls for the use of market assessment of GX investment. Once we have overcome the issues of single-year focus, transparency, and fairness, we will need to start talking about forms of policy formulation and evaluation that do not rely on policy infallibility.

Achieving Carbon Neutrality in 2050

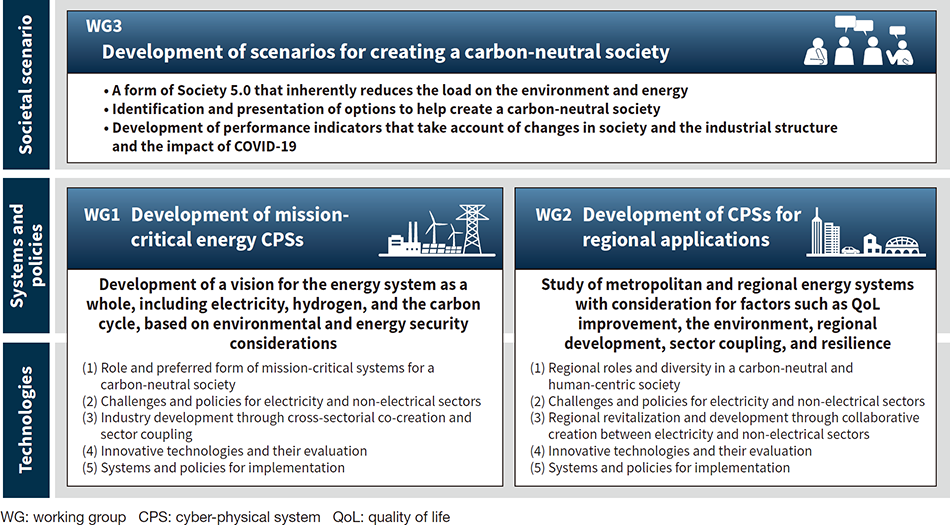

On March 24, 2023, Hitachi-UTokyo Laboratory published version 5 of its proposal entitled, “Toward Realizing Energy Systems to Support Society 5.0”(4). The seven-chapter, 63-page proposal lists a total of 18 declarations under the three headings of geopolitical change, global action on decarbonization, and specific national or regional circumstances.

Making a just transition that also encompasses employment will not only that we develop a clear understanding of what sort of energy transition we will be undertaking on our path to carbon neutrality in 2050. It is also crucial that action be taken around the world on finding ways to encourage behavior change in consumers by addressing greenhouse gas emissions on a consumption basis, instead of a production basis. An essential consideration when it comes to achieving this will be greater transparency regarding greenhouse gases in the supply chain, with the use of digitalization to determine carbon footprints.

If the goal of JPY150 trillion in public and private investment is to be achieved over the coming decade, we will need to look carefully at the fundamentals, namely, the type of policies we adopt and how we go about evaluating integrated policy packages that cover both regulation and support. With the recent passing of the GX Promotion Act marking a shift to the policy implementation phase, there is potential for Japan to become a source of the core technological and policy infrastructure that will lead to the whole world changing its behavior to enable carbon neutrality in 2050, engaging with the Asia region as we do so and remembering the importance of treating evaluation as an integral part of policy formulation. Indeed, this is a time when Hitachi-UTokyo Laboratory needs to be consolidating the wisdom of Japanese industry, government, and academia so as to play a leading role in GX.

REFERENCES

- 1)

- The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), “Study Group on Ideal Economic Approaches for Achieving Worldwide Carbon Neutrality” Supplementary Documents (2021), in Japanese.

- 2)

- Prime Minister’s Office, “Agenda of Inaugural Meeting of Working Group on Agile Policy Formulation and Evaluation,” in Japanese.

- 3)

- Agency for Natural Resources and Energy and Industrial Science and Technology Policy and Environment Bureau, METI, “Investigation into Formulation of a Clean Energy Strategy,” (Dec. 2021) in Japanese.(PDF Format, 8.07MByte)

- 4)

- Hitachi-UTokyo Laboratory, “Proposal: Toward Realizing Energy Systems to Support Society 5.0” Version 5, in Japanese (Mar. 2023)(PDF Format, 7.12MByte)