September 2020

Self Made Man People today are living in a new era in which they can shape their own destiny and make the most of who they are.

People today are living in a new era in which they can shape their own destiny and make the most of who they are.

We are currently going through a period of major transition as we seek new ways of living and organizing society in an era of 100-year lives.

Fifty years was considered a typical lifespan in Japan for several centuries until the mid-20th century. Life expectancies rapidly increased during the latter half of the 20th Century to the extent that we now talk about lifespans of 100 years. While this has led people to focus on the problems associated with the population aging, like pensions and dementia, shouldn’t this doubling of the length of human lifespans also be seen as a paradigm shift where we can look forward to and seek out unprecedented new opportunities?

The transition to a society where people live for 100 years poses three major challenges relating to individuals, society, and industry, respectively.

For individuals, the question is how best to live a life that is 100 years long. Life plans followed a much more predictable pattern when people could only expect to live for 50 years. For men it meant leaving school, getting a job, and working until retirement; for woman it meant marrying by the age of 25 and then raising children. Diverging from this predetermined path was not easy. In the modern era, however, these social pressures have eased, and people can plot out and steer their own path through life. Like a field that produces two or three crops per growing season, it is quite possible to pack a number of careers into a single lifetime if it lasts for 100 years. While there is considerable scope for uncertainty and confusion given that the models for this type of life have yet to be established, in my own opinion it represents a degree of freedom people could never have imagined in the past. This ability for people to shape their own lives, maintaining good health and making the most of their abilities, represents a great opportunity that all of us alive today have the chance to seize.

The second type of challenge relates to how to build a society that is in harmony with the new approach to life described above. One example is that, whereas a lifetime of ongoing learning is essential if we are to live a life that we have mapped out for ourselves, compared to other developed nations, Japan’s current youth-focused education system still puts considerable obstacles in the way of adults returning to university or other forms of study. Under the current employment system, which features lifetime employment and seniority-based advancement, the work people put in during their younger years is rewarded by their eligibility for a pension once they reach retirement age, an arrangement that offers no openings for people to pursue a new career.

This disconnection has come about because most of the structures of current society were built when the population was much younger, characterized by pyramid demographics, meaning a large base of young people with the elderly making up only about 5% of the total. This goes beyond the societal systems of education, employment, and healthcare, also applying to infrastructure such as transportation systems and housing. One example is that the timing of pedestrian crossing signals is based on the walking speed of young people, with the result that half of elderly women (75 or older) are unable to cross the street in the available time. Addressing these issues and transforming the infrastructure of society to better suit its aging demographics is an urgent task.

The third set of challenges relate to industry and address the question of how we can produce products, services, and systems in ways that will provide smart solutions for the challenges of individuals and society described above. The aging of populations is a worldwide phenomenon and one that all nations are destined to face, albeit with varying degrees of time lag, as demonstrated by recent talk of how it is even becoming an issue in Africa. Of particular note are the elderly in Asia, who make up about 60% of the world’s total. As China and the nations of Southeast Asia are experiencing their periods of rapid economic growth and population aging at the same time, the latter issue is one for which they have done little to come to grips with. In the hope of adopting those policies that work best, they have been paying close attention to what is happening in nations like Japan, South Korea, and Singapore that precede them in this demographic transition. If Japan, as a front runner in this trend to longevity, can lead the world in coming up with ways of addressing these challenges, the global market that awaits will be quite large.

I have studied gerontology for many years from the standpoint of social psychology. Gerontology derives from the Greek ger?n, meaning ‘old man,’ as written about in de Senectute by the philosopher Cicero in Ancient Rome, and the term has since the 1900s come to be used not only in philosophy, but also in science.

The field started out as a branch of medicine concerned with the extension of human life, covering topics such as elucidating the mechanisms of aging and overcoming lifestyle diseases. Life expectancies started to lengthen rapidly and reached 70 years during the 1970s. While this may look at first glance like gerontology had achieved its goal, the reality was that the elderly had become a problem for society with many of them being bedridden. Even among those who remained in good health, the majority led inactive lives with little to do.

From this time, the focus of gerontology shifted away from longevity (the quantity of life) and toward enhancing the elderly’s quality of life (QoL), asking how best to keep older people healthy and enjoying a fulfilling life. As achieving this goal presupposes the addressing of numerous challenges that relate to society as a whole, it necessarily involves a multi-disciplinary collaboration of engineering, economics, education, psychology, and others. Thus, the modern academic discipline of gerontology was established.

It was in the midst of this transition, in 1987, that the geriatric specialist John W. Rowe and sociologist Robert L. Kahn in the USA attracted considerable attention for their paper “Human Aging: Usual and Successful” published in the journal Science. Until then the elderly had a negative image in the USA and elsewhere as people who are edging away from society, infirm in both mind and body and living out their remaining years in a rocking chair. In contrast, Rowe and Kahn presented an active and positive image of old age, proposing three conditions for successful aging: avoiding disease and disability, high cognitive and physical function, and engagement with life (this latter involved continuing to have a purpose in life by remaining socially active to the very end, including by contributing to society). The paper garnered wide attention and the question of how to achieve these conditions has become a major focus in academia and elsewhere. A collection of research work funded by a large investment from the MacArthur Foundation was subsequently published as a book and gained a significant degree of traction among the general public, leading to the emergence of the present-day ideal of the “active senior.”

The trajectory of gerontology went through another shift in 2019, last year. While most debate up until that time had been directed at enhancing QoL for the elderly, a society where people live to be 100 is something new for everyone. Having proposed the necessity for a “New Map of Life” that seeks to look ahead and ask how to live such a long life, the National Academy of Medicine in the USA has started working on policy development and system design aimed at achieving this goal.

If successful aging is to be achieved, it will likely require that the sort of problems that tend to emerge in old age, including health, retirement savings, and loneliness, be dealt with over the entirety of life, from birth onward. It is too late to start rushing about trying to do something about these problems when you have already reached old age. Likewise with social services and systems, rather than implementing stop-gap welfare policies for the elderly, we need to come up with new ways of organizing society itself. A broader scope of research in gerontology has to address these challenges and should prove beneficial when preparing this “New Map of Life.”

As we have seen above, the challenges facing societies where people live to a very old age are a clear and global phenomenon. The need, then, is for solutions and action.

The Institute of Gerontology at the University of Tokyo, where I work, is dedicated to seeking such solutions. Rather than just undertaking research within academia, the institute engages in a mix of research and practice involving social experimentation conducted in the field (called ‘action research’). We work on solutions to regional challenges in partnership with citizens, local government, private sector, and other stakeholders. Our goal is to redesign existing communities to meet the needs of highly aged society. Several projects, such as work places for the second life, life-long learning, frailty prevention, community-based health and long-term-care, transportation, are in progress.

One thing that my involvement in this work has made me especially conscious of is the power of citizens. Community residents are both well aware of the challenges and have their own ambitions for their own ways of life. There are also many people who can articulate good ideas on how to overcome these challenges and fulfill these ambitions.

Among the people engaged in research and development at universities or in the private sector, meanwhile, there are many who are focused on further honing the latest technologies but lack any interest in the people who will use them and how they live their lives. It was when I became concerned about this approach to research and began wondering whether it should not be possible to better harness the power of citizens that I came across the idea from Europe of living labs.

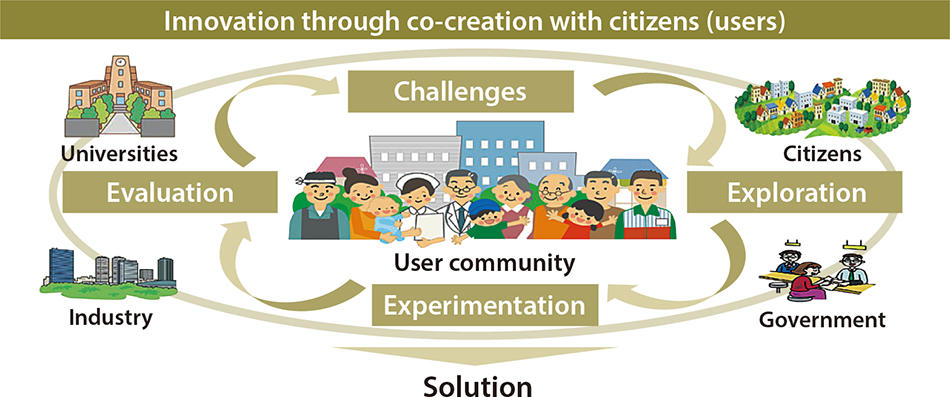

The living lab is a method for user-centric open innovation that was developed in the late 1980s at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the USA and further enhanced in Europe. The method focuses on users and other members of the general public. Utilizing multi-stakeholder co-creation that includes citizens as well as industry, government, and academia, it is an integrated process that encompasses everything from developing a vision to identifying the challenges, coming up with ideas for solutions, building prototypes, running a proof-of-concept (PoC) trial, and ultimately commercialization, with citizens serving a dual role as both a test bed and participants in user co-creation.

Model for Living Lab A living lab provides a venue for innovation through co-creation with citizens.

A living lab provides a venue for innovation through co-creation with citizens.

The Kamakura Living Lab was established in 2017 with the aim of implementing the living lab philosophy and methodology in a Japanese context. The lab addressed the three areas of citizens’ challenges, governmental challenges, and corporate challenges. Like Kashiwa City and many other parts of Japan, Kamakura City is experiencing a high level of aging among the population in residential areas that were developed during Japan’s era of rapid economic growth. The percentage of elderly in Imaizumidai, where the Kamakura Living Lab is located, exceeds 50%, and represents a microcosm of the urban sustainability and other challenges facing a highly aged society.

In this context, what is the challenge that most concerns the community residents? One consistent message that comes out of workshops with residents of various ages is a heartfelt sentiment of wanting their community to be a place where young people as well as seniors like to live. One proposed solution was to create an environment that facilitates telework, with the conversion of unused living space into home offices or empty retail stores into fully equipped satellite offices being among the practical suggestions. A call for corporate participation in achieving this led to a housing company, and an office furniture company getting involved, as well as three information technology (IT) companies. The resulting co-creation with residents included the furniture for home offices. These user-centered products are selling well and have quite a reputation for usability.

The sight of companies taking an interest in the challenges they face came as an unexpected surprise to residents, while the experience of having their ideas put into practice and seeing progress made on overcoming community challenges fostered greater self-confidence and empowerment.

What I found particularly interesting was how a “chain of needs” arose among the residents in the process of creating the solution. “If fathers are going to be at home on weekdays then the town should have such and such facilities…” “If we do that, then this too should be possible…” The highlighting of needs that people had been aware of but had never previously articulated led to a series of practical concepts and ideas for enriching community life being raised among the residents.

This chain of needs represents a treasure chest of innovation. It is one of the benefits of engaging in co-creation with residents, something that would not have come about had the collaboration been limited to only organizations like companies or universities. One could also add that satisfying the needs that arise from a practical sense of what it is like to live in particular communities also forms part of the vision of Society 5.0 with its aim of bringing happiness and wellbeing to everyone.

Companies need to develop an accurate appreciation of citizens’ potential for innovation. While there are people in both the private and public sectors who, despite being citizens themselves, see co-creation with citizens as a risky, difficult, and inefficient exercise that is best avoided, there is a limit to how far innovation can go if those citizens (users) are excluded.

The challenges facing society are complex and, however small an individual challenge may be, they rarely prove to be amenable to resolution through the application of a single academic discipline or the capabilities of a single company. While open innovation has long been practiced, it has been limited in the past to collaboration between companies or between industry and academia. What will be more important than ever in the future, however, will be to take on challenges through the formation of ecosystems based around the objectives of diverse stakeholders, encompassing industry, government, academia, and the public, and in ways that take advantage of their respective strengths. In Europe, this type of co-creation is called “Open Innovation 2.0.”

Ultimately, it is companies that play the crucial roles of coming up with products, services, and systems and of deploying them in practice. What will likely be needed in the future is for these companies to engage with users and government and to participate through all co-creation processes.

The Kamakura Living Lab has been part of an international collaboration with a living lab in Sweden and they have been working on cross-border solutions to the five challenges of aging societies: health, employment, housing, mobility, and loneliness. While differences in culture and institutions have in the past been seen as obstacles to the adoption of successful initiatives from elsewhere, the very fact of coming from different backgrounds prompts a range of different approaches and brings a diversity of perspectives. I believe that having partners bring their respective ideas and engage in a multifaceted debate can show the way to overcoming these problems.

This applies not only to the challenges facing those societies where people live long lives, but also to the global challenges facing countries everywhere. If we are to ensure the sustainability of the global environment at the same time as delivering wellbeing and a better QoL for individuals and for society as a whole, then it is too late for countries or companies to be working alone. What is needed is for those involved to see each other, not as competitors, but as partners in co-creation who draw on their different cultures and strengths to come up with solutions together, acting globally in collaboration with multiple stakeholders and through widespread co-creation that transcends national borders.

This places strong expectations on Japan to show leadership not only with respect to the challenges of a long-living population, but also on problems of peace and the environment. This is because Japan is widely recognized for strengths that include harmonious coexistence with nature dating back to ancient times and a culture of harmony and tolerance. I look forward to seeing Hitachi living up to those expectations, leading co-creation, and driving Japanese innovation.